When I was six years old, we lived in a rented Victorian in the Richmond District of San Francisco for several months, and my favorite time was the Silly Half Hour. There was no set time when this event would occur, and it didn’t happen every day. But once in a while, after Dad and I had cleared the table and left Mom to her nightly task of returning the kitchen to order, we would retire into the adjacent sitting room with the tiny space heater and the radio where on other evenings we listened to dramas, and suddenly it would happen.

When I was six years old, we lived in a rented Victorian in the Richmond District of San Francisco for several months, and my favorite time was the Silly Half Hour. There was no set time when this event would occur, and it didn’t happen every day. But once in a while, after Dad and I had cleared the table and left Mom to her nightly task of returning the kitchen to order, we would retire into the adjacent sitting room with the tiny space heater and the radio where on other evenings we listened to dramas, and suddenly it would happen.

These magical times frequently began with Dad telling a story about a little boy in England. He was the boy in the story, of course. He told me how he used to walk for hours on Shipley Glen with his friends, cycle along the Leeds-Shipley canal to watch cricket games on Sundays after church, and deliver milk on a horse and cart in the dark hours before school.

While my father was concentrating on crafting his tales, I would stealthily take a black comb from his pocket and begin styling his hair, standing behind him on the flowered sofa – both actions that were forbidden at any other time. Dad’s hair, shiny and fragrant with Brylcreem, was always parted down the middle, and he normally hated to have anyone touch it. Once I had the comb in my hand, however, I would send his hair straight back, trying to make it into a pompadour like the ones I had seen on posters of film stars. When that didn’t work, I would comb the strands forward into his eyes, sending my mother, peeking around the kitchen door and trying hard not to smile, into peals of laughter. I can still remember the oily feel and sweet fragrance of Brylcreem on the comb and on my hands.

When he had had enough of my grooming, Dad would play “horsies” with me. Because we had left all of our furniture in Australia, most of the rooms in the cavernous house were empty, affording us a magnificent playground. Dad would crawl around the sitting room on his hands and knees with me on his back. Somehow he’d manage to turn the doorknob, and burst into the hallway. During that period of my life I was often dressed in my black Hopalong Cassidy cowgirl outfit, the one with the silver trim and the white fringe on the skirt. Soon I was whooping and hollering and brandishing my two silver pistols. During Silly Half Hour I was allowed to be physical and loud, and . . . well, silly — all behaviors that had been forbidden to me previously, when we had lived mostly in no-children-allowed apartments, and especially during the year and a half we had lived with my grandparents and aunt and uncle and cousin in Australia.

Down the long hall Dad and I would gallop, into the empty parlor, through the long dining room and into the connecting great room with the triple bay window, then back out into the hall. As an only child with few playmates, I was in heaven. The thread-bare carpet runner in the hallway must have hurt my father’s bony knees, but he never complained.

My mother generally took no part in this evening ritual except to utter “tsk tsk” from the sidelines and periodically warn my father to be careful, adding “She’ll never go to sleep tonight.”

We paid no attention. Dad and I rolled around on the floor together, tickling one another and giggling. We called each other silly names. He gave me piggy-back rides. I gave him gentle noogies. We laughed. Oh, how we laughed. Sometimes Dad would ride my tricycle down the hallway. I would jump out of one of the three bedroom doors crying “boo!” and he would feign terror, or I would ride the trike and he would crawl along behind, making wolf noises or pretending to be the Lone Ranger about to capture the bad guy.

At no other time in my life did my father behave like this. Once our lease ran out, we left San Francisco and moved to the suburbs. Dad began to work overtime at the cabinet shop where he was employed, and then until late at night in the garage making knick knack shelves for neighbors. My parents acquired a mortgage, and then a second child, and what had been our silly half hour became a story, a good night kiss, and a promise to go fishing on the weekend — a promise that was kept at first, but that soon fell by the wayside. For the rest of his life, my father remained a dedicated wage earner and a devoted father, but never again did he crawl on all fours or ride a tricycle.

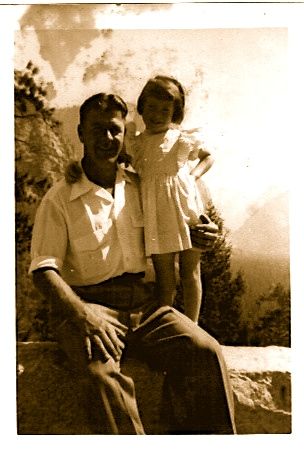

Looking back over his 91 years, I realize that this brief time of silliness is probably what sustained my love for him during the difficult times, when I made life choices he didn’t understand, or when he began to slip into the confusion and paranoia of dementia. Now that he is gone, I am comforted to remember him as he was during that enchanted time – my very strong, very silly, very loving Daddy.

Share this post