Why Should We Read Classic Books?

I have recently learned why I love great literature, and why we should read more classic books.

- Classics are timeless. Classic fiction contains thought-provoking situations that present its characters with sociological and ethical dilemmas. Considering those dilemmas causes the characters — and readers — to wrestle with conflict and difficult decisions that eventually lead to personal growth. Considering those dilemmas in the modern context, we may draw similar or different conclusions — it is the thinking that matters. Gifted child educator Lisa Van Gemert writes “It’s good for your mind to read books that have strong ideas.” That is true for gifted children, but also for all children and grownups.

- Classics are language-rich. My friend Nicholas reads Dickens for fun. It is relevant that he is writing a novel set in the 18th century, but we all can appreciate, and learn from, the colorful language in books that Dickens penned:

- “The pain of parting is nothing to the joy of meeting again.”

- “A day wasted on others is not wasted on one’s self.”

- “The most important thing in life is to stop saying, ‘I wish” and start saying, ‘I will’. Consider nothing impossible, then treat possibilities as probabilities.”

- Classics force us to think deeply and concentrate. Spencer Baum, the founder of the Facebook Group, Deep Thinking About Great Books, calls classic literature “essential medicine in the Age of Social Media.” It is well known that our dependence on digital devices is shortening our attention spans. Baum points out that it also teaches us to skim the surface of ideas, making us shallow thinkers. Reading classic literature, he writes, is the opposite experience.

My Love Affair with Books

Since I was a child I have always loved books. When I was five years old my mother took me to the San Francisco Public Library to get a library card, and whenever we moved to a new community the library was one of the first places we explored together. The summer I turned ten I volunteered to work in our local branch library, mostly shelving returned books and straightening the displays. Following each day I worked, I lugged a half dozen books home. During summer vacation, those wonderful twelve weeks of no school and – in those days – no organized activities, I would climb a tree in our neighborhood after breakfast and read until noon. One summer I worked through all the Nancy Drew mysteries, then started on Hardy Boys, provided by my best friend Mike Lacey, whose father built the wonderful tree house in which we read.

As a parent and a teacher, I sought out high-quality books for children, and selected my favorites to give at baby showers and children’s birthday parties. I taught Children’s Literature at the local community college, and eventually, when I had my own children, I read magical stories to them every night.

The Book Club Effect

When I moved to Santa Cruz in 2011, my daughter invited me to join her book club, which was primarily made up of women she had met at the attorney’s office where she worked. For a decade, my reading was heavily influenced by the New York Times Book Review and the displays at Bookshop Santa Cruz. We read edgy books, books that educated us about other cultures, and books written by movers and shakers. My participation in that book group broadened my knowledge of public affairs and made me think.

My experience in that book club, which folded during Covid, led me to join a book club sponsored by the Calabasas Library when I moved to southern California a year ago.

Which is how I came to be reading Farhenheit 451.

If you are close to my age you probably remember reading this book in high school. I fear its message went right over my 15-year-old head, as it may have done yours. Or perhaps not. Reading it again after a lifetime of reading, selecting books for others, and responding to periodic book banning, I realized that this book, published in 1953, is as relevant today as it was when Ray Bradbury wrote it.

“Too depressing,” one of my friends said. “A society where firemen burn books. I couldn’t finish it.”

I disagree. If you read all the way to the end you learn that the fireman who is the main character comes to understand the value of good books, and meets others who work to save those books. The message in this 1953 book resonates today just as it did when it was written, and I pondered it for several days.

Going Forward with the Classics

Reading Fahrenheit 451 reminded me that classic books can speak to readers in many times and places. While considering the message of Bradbury’s book, I came across an essay by Spencer Baum, cited above. The closing paragraph of his essay explained why I was spending so much time thinking about the story Bradbury had crafted:

To read a work of classic literature is to engage with the best work of the best minds, and do it in a way that challenges you to be better, to seek out and appreciate beauty, to ponder the big questions, to follow a line of thought, to concentrate, to transform symbols of language into an image in your imagination, to weigh assertions, to analyze, to exercise your faculties of reason.

Try getting all that from an Instagram post!

Italo Calvino, one of the most important Italian fiction writers in the 20th century. argues that we should dedicate part of our adult life to re-reading the classics that shaped us as children. In fact, he says, “reading in youth can be rather unfruitful, owing to impatience, distraction, inexperience with the product’s ‘instructions for use,’ and inexperience in life itself.”

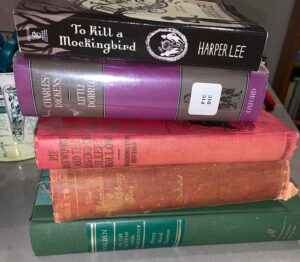

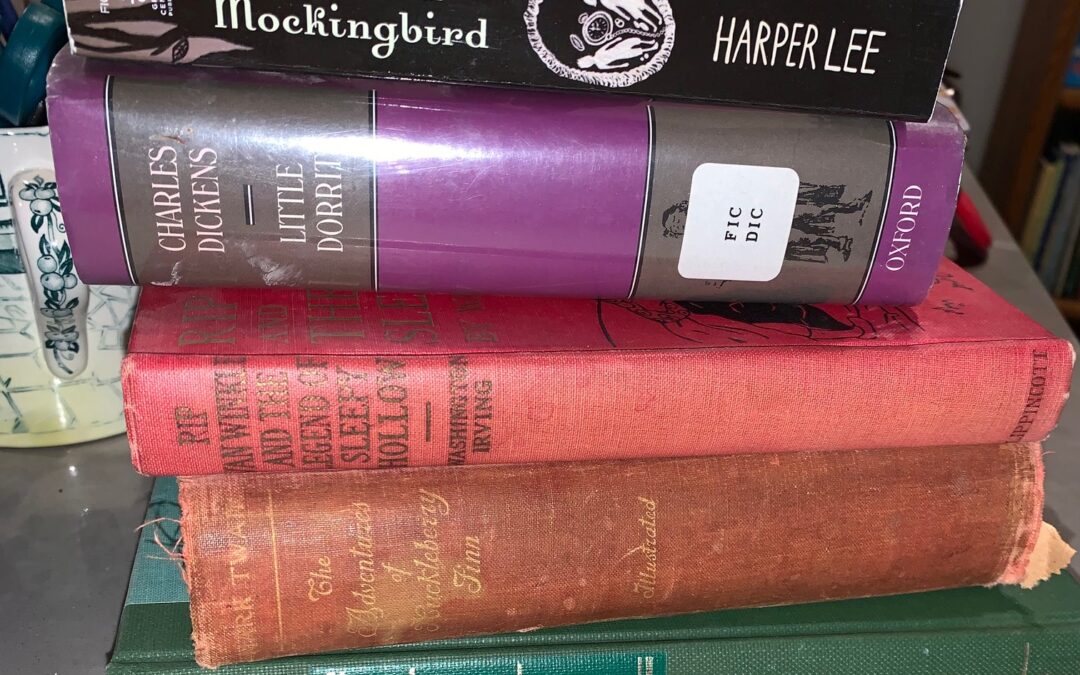

Which is why I plan to spend the rest of the summer digging into some of these classic books that made it to Calabasas with me:

To Kill a Mockingbird – Harper Lee

Little Dorrit – Dickens

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle – Washington Irving

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn – Mark Twain

Walden and On the Duty of Civil Disobedience – Henry David Thoreau

I encourage you to search your own bookshelves and share your finds with us. What classic books will you read in the coming months??

Consuelo,

I think our mothers had a lot in common. We were fortunate.

Thanks for the reminder about the classics. As I read your early experiences reading over the summer I was transported to my own childhood, where my Mom, who could not read in Spanish or English (she never went to school, but such a wise woman) would give me a few coins to buy books at the second-hand store in Watsonville. Such beautiful & vivid memories!

Thanks, Marlene,

I enjoyed reminiscing with you a bit, as I considered some of the joys of my reading past. I suspect that while you were devouring Nancy Drew, I was deeply involved with Edgar Rice Burroughs. My favorite haunt in Seattle was the old 3-story Used Book Store on 2nd Avenue, where I spent most of my allowance.

I have often wondered and never resolved for myself the question of who decides and how what makes a Classic.

Erik,

Thanks so much for your comments. I can’t illuminate your query about what makes a classic, however. Over 30 years works for cars, but I’m not sure about books. I don’t think merely age makes classic literature; it needs to have depth and breadth and timelessness, right?

Hi Marlene:

Thanks, your blog has done it again for me. I agree that re-reading certain books you see a totally different perspective. Sidhartha by Herman Hesse has done that for me. To Kill a Mockingbird is another one. At the moment, I am writing a proposal for CaAEYC Conference ” How to Choose and Use Good Books”. The intention is to develop a Workshop around deciding what is good material for young children and how to present it to provoke critical thinking. Will develop the workshop (with a few friends) whether CaAEYC wants it or not because we see a need for it. Been reading Bell Hooks “Teaching Critical Thinking – Practical Wisdom” and she makes the case so elequently about how that is not taught in our US schools for the most part. We are not raising a country of readers. Have to change that and as you know, it starts with developing a relationship with books at an early age.

Gaby,

I’m excited to learn about your CAEYC proposal — if it were up to me I would approve it in a heartbeat. Your statement “We are not raising a country of readers” resonates with me. It isn’t hard to raise a reader, but it helps if you are a reader yourself, and the whole news via internet culture works against deep reading.

Great post, great message! I read Dickens because he devoted his life, pushing himself to the very limits of his brilliant abilities, to make use of the English language in a unique and personal way—all the richest, most creative, and diverse ways he could—leaving an articulate and erudite legacy of who he, and the world he lived in, was, and that world is precisely the world we live in today (just without all the stuff that has happened since, yet still connected as part of the whole continuum of civilization).

Thanks, Nicholas!